Photo by Ross Halfin

Heavy metal was a mistake. Or, at least, was based on a misunderstanding. This view is expressed by Black Sabbath bassist Geezer Butler in his memoir, Into the Void: From Birth to Black Sabbath and Beyond. When Black Sabbath’s self-titled album was released in 1970, their name (admittedly taken from a 1963 horror movie) and the album’s foreboding cover (depicting a witch-like figure standing in front of Mapledurham Watermill in the English countryside), convinced people the band members were occultists. Sabbath were bemused by the suggestion.

“Because of the name, everybody, especially when we got to America, automatically thought it was satanic and all that stuff,” Butler tells me down the phone from his home in Utah. “We never wanted to be like that, because there was a band around when we were coming out called Black Widow. They used to do all these fake sacrifices. We used to think it was really corny. We didn't want to be known like that. So the very first lyrics, to the song ‘Black Sabbath’, are a warning against all that kind of stuff.”

Black Widow once performed one of those mock sacrifices with Maxine Sanders, the wife of self-styled “King of the Witches” and Wiccan, Alex Sanders. It was Alex Sanders who warned Sabbath that they were about to be hexed by real Satanists. It prompted Sabbath to seek protection by wearing crosses made of aluminum, fashioned by singer Ozzy Osbourne’s father. It wasn’t enough to ward off the scathing reviews they received for their debut album. One publication described it as “bullshit necromancy”.

But, luckily for us, it was too late. A generation of music fans were enthralled by Black Sabbath and ran with the darkness of the imagery, spawning the heavy metal genre and its many subgenres. Despite his insistence they didn’t dig Satan, Butler himself first used the devil horns hand gesture onstage during the late sixties. He gave Ronnie James Dio his blessing to use it too, after Dio replaced Ozzy as Sabbath singer for Heaven and Hell in 1980, and was fretting that he shouldn’t copy Ozzy’s habitual peace signs onstage. The devil horns became synonymous with Dio and heavy music itself. Dio popularized the symbol, but Butler quietly innovated it.

The irony is that Sabbath were much more influenced by Christianity than Satanism, specifically Catholicism. Butler’s book even reveals that Sabbath song “Iron Man” is actually about a vengeful Jesus Christ.

Butler was born on 17 July 1949 – the seventh son of a seventh son, no less – to Irish parents. The family were devout Catholics. One childhood memory of Butler’s was a missionary visiting their church, delivering his sermon from the pulpit in a black cloak with his arms aloft. He looked, as Butler writes in the book, like a “giant bat in flight”. This combination of the devout and devilish was seared into Butler’s young mind.

“I mean, the first thing I ever remember seeing is Jesus nailed to a cross,” says Butler. “It's a bit of a morbid thing when you're a little baby. You start perceiving things, and you see this figure nailed to a cross. You think, ‘Oh God.’ My family always had these pictures of Jesus, heart exposed, and Mary, and all that kind of thing. Catholics really do go into the imagery. Seeing that bloke like a bat, he looked like Satan to me. Because he was terrifying. He really was. He was screaming at everybody in church. Saying, 'You're all going to hell!' and that kind of thing. It sticks with you.”

As Black Sabbath’s lyricist, Butler used his words, as sung by Ozzy (“he made my lyrics sound as if they were coming from his soul,” Butler writes), to tackle the grim social reality around him. The band was from Aston, part of Birmingham, in the Midlands region of England. As he notes in the book, the Nazi Luftwaffe paid special attention to this industrial center, bombing large swathes of it during the Second World War.

Sabbath, with Tony Iommi on guitar and Bill Ward on drums, were the children of the war generation. A generation that was traumatized and reluctant to share their feelings. When Sabbath roared into life on “War Pigs” and its ilk, songs that sounded like actual warfare, it could be interpreted as children reflecting their parents’ generational trauma back to them, in the only language they knew how.

“I never really thought about it that way,” says Butler. “Because of not knowing much about what they'd been through, it was more us looking to the future and what we were wanting to do with our lives. When they [his parents] were gone there were so many things I could have asked them but never did. Same with my brothers, really.”

Butler was a “weekend hippy” in his teenage years, attending the Festival of the Flower Children at Woburn Abbey in 1967. A photograph of him included in the book, wearing beads and a flowery hat, was published in a tabloid newspaper at the time. Butler used to walk around in a yellow satin shirt, dyed green boots, a green corduroy jacket and a tatty old fur coat. But as the sixties soured and Sabbath formed, he took it on himself to express the disquiet felt by many of his peers.

“The lyrics were about the stuff that we were going through at the time,” he says. “People in the late sixties/early seventies were becoming aware of pollution and climate change and all that sort of stuff, even though some don't particularly believe in it now. But it was a big thing back then. A lot of the lyrics were about that. Some of the lyrics were about what was going on in Northern Ireland at the time – the Troubles. I didn't want to preach to people, but I wanted to put over what I was thinking: maybe this could be a solution to what everybody's going through.”

The song “After Forever”, from 1971’s Master of Reality, was directly about the Troubles. It was scathing of both sides of the Catholic and Protestant divide. “I think it was true it was people like you that crucified Christ,” Ozzy sings. One line in particular got Butler into hot water with the press, and his father: “Would you like to see the Pope on the end of a rope – Do you think he’s a fool?”

The song was a sophisticated critique of religious violence at the height of the killings in Northern Ireland. It was a conflict that further blighted his family, when the IRA bombed two pubs in Birmingham in 1974. His father had to leave his part-time job due to the abuse he received. The Irish were personae non gratae on the British mainland in the mid-seventies.

Butler’s relationship with his father is a prominent thread in the book, and also reveals how he could get caught between worlds. Sabbath were a working-class band. Their story is as much about their naivety entering the cut-throat music industry, how they were screwed over by managers and other business people, as much as what an incendiary creative force they were. When the band did have money, they struggled to know how to spend it appropriately. On one occasion, Butler visited his father in his new Rolls Royce. He was staggered at the reception he received.

“‘Don't you ever come to my factory again in that bloody car!’” Butler remembers him shouting. “He was disgusted. I started realizing that I'd gone from working class to pseudo bloody whatever it was, middle class or whatever. It just really brought me back down. Because, otherwise, you think you're something that you're not, and it really taught me a lesson.”

The poverty of his childhood contributed hugely to Sabbath’s sound (“of course we sounded dark and heavy, this was our lives,” he writes). Butler’s first acoustic guitar only had two strings, because he simply couldn’t afford to replace them with a full set. It was this way he developed the busy, wandering, blues-box style of bass playing that became the signature of Sabbath, interweaving with Iommi’s thundering power chords and wrung-to-death riffs.

“Being restricted to two strings means you make a lot of that kind of thing,” says Butler. “You learn different styles to what anybody else is learning.”

As well as the grittiness of his early life, and with his bandmates – who he writes “fought like wounded animals” with one another – there was Butler’s internal world. Into the Void is frank about his lifelong depression. He describes distressing times growing up: when he deliberately stepped out in front of a lorry; injured himself so badly self-harming he bled everywhere; and wanted to climb into a grave alongside his dead dog. Years later, during the Ozzmosis album tour, he describes his drinking and depression changing his personality from the “old” him into “this other me, someone who didn’t want to talk to anybody.”

There’s an uneasy truth that Sabbath’s lyrics and music might have been very different if Butler had received the support he needed for his mental health earlier.

“It would have made my life a lot easier,” says Butler. “But I think a lot of the lyrics I wrote were inspired by those black holes. The only way that I could express myself. I mean, everybody gets down, but when you get clinically depressed, you can't explain it to anybody. The lyrics to ‘Paranoid’, for instance – that was the only way I could reflect what I was going through at the time. When I'd get depressed, some people would say, ‘You're a miserable bastard,’ and things like that. ‘Come out of it, go and have a drink.’ And then I go to the doctor, and he'd say the same: ‘Go down to the pub, have a couple of pints, you'll be alright.’ No, that's not gonna work. Unless you've been through real depression, you can't explain it. It wasn't until years later in 1998, or around then, that I actually went to a proper place in St. Louis, told him what I was going through, and he actually knew my situation: clinically depressed, go on Prozac for six weeks, you'll start feeling normal again.”

When Butler did try to write his way out of a depression he produced a handful of some of Sabbath's greatest songs. Alongside “Paranoid”, Sabbath’s best-known song, he mentions “Hand of Doom” and “Symptom of the Universe”.

“It just helped at the time,” he says. “It was a way of expressing what I couldn't express verbally to anybody else.”

In the book, Butler describes “Symptom of the Universe” as a song about “love, belief and fate”. As chaotic as the Sabbath story gets, Butler is a firm believer that the way they got together, four poor local lads who loved music, had to be predestined.

As crucial to Sabbath’s story and music are the dream visions Butler experienced. He woke up one morning aged twenty with the lyrics and main riff to “Behind the Wall of Sleep” (from their first album) fully formed in his head.

Sabbath’s music is supernatural, considering the wider musical landscape of the time. The first two albums came out of nowhere, in quick succession in 1970, like something was playing the music through them. Even today, over fifty years later, they sound remarkable.

A visitation from a shadowy figure at the foot of Butler’s bed inspired the first line of the song “Black Sabbath”: “What is this that stands before me?” The book opens with Butler awakened at six years old by a glowing sphere in which a man with silver boots and long hair is playing guitar: a vision of his future self.

Some of these hypnagogic hallucinations could be accounted for by sleep paralysis. It's a condition where the mind gets stuck between a sleep and waking state, and can result in lucid visions. Over history, sufferers have reported waking to find a horrible old woman or goblin sitting on their chest and constricting their breathing, or seeing bright lights and alien spacecraft.

“First I really heard about it, what you just said,” says Butler. “Yeah, that totally makes sense. To explain the things that happened to me, people either think you're a lunatic or making the whole thing up. It does explain a lot.”

But he counters that it doesn’t explain how he dreamt reading the contents of a letter from a girlfriend, before he received and opened it for real, and discovered it was the same – word for word. Something runs a little deeper with Geezer Butler.

Into the Void makes it clear that Sabbath were bonded like brothers. Iommi was an alpha male, from the year above Ozzy at school and the band’s leader. That dynamic never left the pair and defined the power struggles over the right to use the band’s name, and other issues, over the years.

Sabbath often behaved badly, even managing to upset grungy space-rockers Hawkwind at the state they’d left the Rockfield residential studio in rural Wales, where they recorded the Paranoid album. Sabbath had had a flour bomb fight in the studio and wrecked the table tennis table. “Who knew Lemmy was a ping-pong enthusiast?” Butler dryly notes in the book.

Bill Ward, one of the greatest and most distinctive drummers in rock history, was the designated fall guy. From having fireworks shot at him in bed, to being coated in gold and lacquer, which nearly killed him. Now totally offline, Butler hasn’t spoken to Ward since the band won a Lifetime Achievement Grammy in 2019. Butler has acted as confidante to both Ozzy and Iommi, though now only communicates with Ozzy via text and hasn’t spoken to Iommi since last year. Disclosing what they've meant to each other isn't how they interact.

Instead, they often let their fists do the talking. There have been multiple violent skirmishes in their history: from a fracas with Doc Martens-wearing skinheads in an English seaside town (which inspired the song “Fairies Wear Boots”), to taking on the entire staff of a Barcelona restaurant after a night of Ian Gillan, then singer with Sabbath, repeatedly pouring peanuts down the waiters’ trousers. Smashing a vase against a wall that night earned Butler a large gash in his finger. He had previously broken a finger punching a TV in Japan. Iommi is mythologized for slicing off some of his fingertips in an industrial accident, but Butler seemed to subconsciously perceive damaging his own fingers as a competitive act.

“It's the way you grow up,” Butler says of the band’s fighting. “Not the nicest of areas to grow up, back in Aston. That's what you're used to – you're always ready to have a scrap. It's not like now, with all the bloody knife crime going on. Dad always said if you knock somebody down, never, ever, kick them while they're on the floor, because only cowards do that. That's the kind of rules that you lived by back then. But then, when we went on the road, looking the way we did and everything, you go into a club and immediately you know if some girl fancied you or whatever, that their boyfriend would naturally want to beat the hell out of you. Just looking like we did, going into various places, people just seemed to want to pick on us. But I avoided it as much as I could.”

Before the original line-up reformed in the late nineties, Butler was working with Ozzy on his solo material, and his own band. He was absorbing the tougher, “ultra-heavy” sounds of the era. His first solo album in 1995, Plastic Planet, recorded with Fear Factory’s Burton C. Bell on vocals, is a crushing testament to the period. It’s still a mighty album. Opening song “Catatonic Eclipse” has a verse riff which has the plunging intensity of a breakdown by the toughest hardcore acts of today. Its lyrics built on the ideas Butler introduced on Sabbath’s Dehumanizer album song “Computer God”, about a digital deity, with humans as merely its programs.

“I really liked Fear Factory at the time and I'd been writing all this stuff that was too heavy for Sabbath or Ozzy,” says Butler. “Pedro [Howse, guitarist], my nephew, had this band called Crazy Angel, who were like an ultra-thrash band. So when me and him got writing together it came out ultra-heavy, and I wasn't restricted to what lyrics I was going to write about. A lot of it is about science fiction – a bit like what's going on now with the AI stuff and everything.”

Butler has long been a prescient songwriter. The first track on the Sabbath compilation put together in 1995, Between Heaven and Hell: 1970-1983, opens with “Hole in the Sky” from 1975 Sabbath album, Sabotage. On it, Butler takes in the rise of China (“I’ve seen the western world go down in the East”, the damage of gas-guzzling vehicles (“I don’t believe there’s any future in cars”), and the downright metaphysical: “Hole in the sky/Gateway to heaven/Window in time/Through it I’ll fly”.

When the original Sabbath re-emerged and toured America under the Ozzfest banner in 1999, Butler was alive to the new generation which sang his band’s praises. It was a welcome, yet destabilizing, change from the derision, verging on outright contempt, they received at the outset of their careers. Fear Factory headlined the second stage that year, with a rotating order of support bands, including a new act from Des Moines, Iowa, called Slipknot.

“I was really into metal back then, and it was influencing the stuff I was writing as well,” says Butler. “It was amazing to see what new bands were coming out then. And each one had a different version of metal, if you want to call it metal. Different versions, instead of just going on and screaming into the microphone and everything sounding the same. Really good, different bands coming out. Slipknot being one of them, obviously. It was great.”

But the way in which the band was treated in the 1970s remains a source of regret and pain for Butler.

“The main thing that… well, it didn't hurt, but it was sad, was that we were taken for such suckers when we first started,” he says. “We were just treated like these four idiots from Birmingham that don't know anything about business, so we'll just completely take advantage of them. All we wanted to do is get a record out. We'd have sold our souls and we practically did. We gave it all away really. It wasn't until the 1980s that we started to get it all back. So that was sad.”

The flip side of that is the resilience the band showed in the face of that hostility. Sabbath could have thrown in the towel many times in the early days. Now, they are revered as metal godfathers, celebrated with a monument in their home city, and the reason metal exists and you’re reading this piece in the first place.

“I’m proud that we've been against what everybody told us,” says Butler. “It was really tough trying to get a record deal back then. And we literally didn't get one until the seventh person that we did an audition for finally said, ‘OK, I'll give you enough to do a couple of days in the studio.’ And they gave us 500 quid to go and record the first album. I'm really glad that we stuck with it. Nobody gave us a chance in the early days. So I'm proud that we all stuck to our guns and didn't listen to them.”

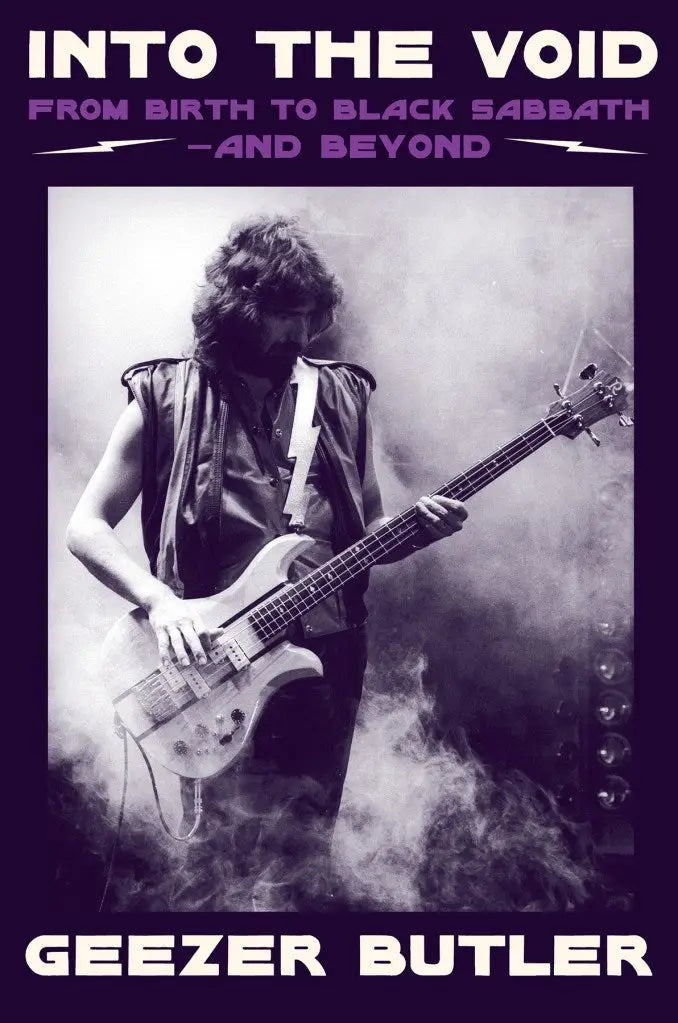

Into the Void: From Birth to Black Sabbath and Beyond - a memoir from Geezer Butler is now available via HarperCollins. Order the book - HERE