When does a concert become a ritual? When does a band performing a sequence of songs morph into something communal, intuitive, and darkly magical?

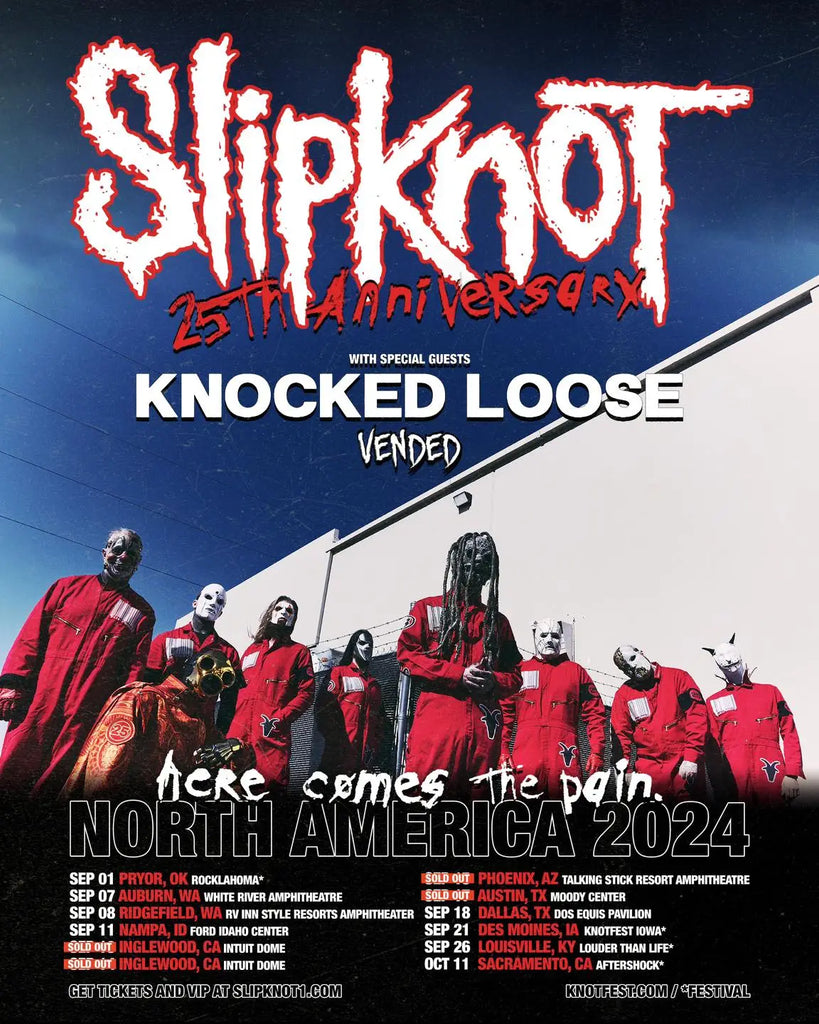

Ask anyone who’s been to a concert on the first leg of Slipknot’s Here Comes the Pain 25th anniversary tour and they’ll tell you: It’s during “Scissors”. The final track on Slipknot’s epochal self-titled album, “Scissors” is nothing less than a seance.

During the song's recent live outings, it’s as if the band is resurrecting its past, and its demons. But, according to clown, it only works when the configuration of the nine members performing it is right. There’s a reason it has lain dormant for the best part of a quarter of a century.

“The fact that we're doing ‘Scissors’ means that we have 190% [sic] belief in us again, and Eloy can do it,” says clown. “Eloy is believable. I am in tears most of the time. I do nothing in ‘Scissors’. Zero – I do zero! Now, what I did do was weld the fucking thing that makes the sound in the beginning [which tortilla man uses onstage]. I did some things. I could play. There's parts. But ‘Scissors’, for me, is a way to unlock one's own unselfishness, to be a part of greatness, and just be without having to be.”

The recorded version of “Scissors” is eight-and-a-half minutes long. Its oblique, sealed-coffin claustrophobia comes from its ragged structure, blanketing layers of distortion and bleak allusions to self-abuse.

“I play doctor for five minutes flat,” Corey intones at its beginning, in the most hushed voice he uses on the album. The song follows this prescription, widening out after its fifth minute – a nightmarish vista into which Corey pours a fractured psyche.

Live, in 1999, this is where the band would embark on a distended improvisation of bowel-scraping guitar drones, punctuated by furious drums, as if the song and band had entered a fugue state. Corey implicated the audience in the song’s psychodrama. “I am the hate you suppress,” he said spontaneously during this section on 1st December 1999, in Minneapolis. Eventually, by the time the band returned to Europe to tour again in March 2000, “Scissors” had reached almost double its original running time.

Slipknot was practicing a kind of black magic at this point. Sickened, abrasive psychedelia that teetered on the absurd. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that a month later, on 8th April in Montreal, they introduced the ‘Jumpdafuck!’ breakdown of “Spit It Out”. This broke the stranglehold spell of “Scissors” over the set. Slipknot entered a more palatable phase of crowd participation. But now, during this tour, the band has dispensed with the jump-up section of “Spit It Out”.

Bringing “Scissors” back in 2024 is not simply Slipknot commemorating an anniversary, but ritualising their performances again. Once they end the set with the song, there’s no going back. There’s no goodbyes and barely a chance to wave. They can’t follow that intensity.

The song is also the key to understanding the upheavals in the band’s lineup over the past year.

“I mean, Corey has been laying on his back [performing the song]. That's not acceptable in a normal Slipknot mentality. You only get that feeling of acceptance when the band is a band, and we haven't been a band for a very long time now,” says clown.

“What does that mean?” clown preemptively asks before I have the chance. “That means that we always do the best we can, and we always try to make what we have work. Okay, that's what's great about us. I mean, we don't give up on anything, even ourselves. The fact is, there's a business out there. There's a way the ferry runs, there's a way the bus fuels, there's a way the airplane lands, all these things I can't control. So while you're trying to make the art everything you want, you've got this outside world making it hard to work. Slipknot just decided we're going to start working again, and we made changes. There's a lot of changes, more than just the one change I'm sort of swirling around, because that's not the only change. Nobody gets that much fucking credit, okay? It's all of us.”

There’s a channeling taking place within Slipknot, of the spirit of 1999, without subscribing to the lie of trying to wholly recreate it. The only way for clown to approach it is as Slipknot in 2024. He is adamant that he won’t fail by pretending to be the person he was back then. At 54, his body doesn’t heal like it used to. Front flips and backflips are out. Tossing a coin backstage – to see whether he or Sid gets punched in the face – is out. Asphyxiating himself with his mask and feigning masturbation during “Scissors”? Let’s see what happens during the tour’s second leg.

Staying truthful to the ritual of Slipknot 99 in 2024 isn’t without pressure. When Slipknot changes its formula and drops certain songs from its setlist, there are reverberations throughout the business side of what they do, right down to the water in the bucket to clean the floors of the venues. But then there’s art, and dedicating oneself to recreating a moment that is as truthful today as it was then.

“I get goosebumps when we start going off on that trip like we used to,” says clown of “Scissors”. “We go off on this trip, and it goes and it's real. It's not programmed. It's not like we're forcing it, and everyone’s like, ‘Go and play ‘Scissors’ and get weird.’ No, no, no, you don't do that. You don't ask God to come out and pretend ‘Scissors’ and then leave, and then come back and play ‘Duality’, ‘Psychosocial’ and ‘Before I Forget’, just so you're all happy. Are you kidding me?!”

Talking to him, clown is the loquacious, business-minded, and slightly more ironical version of himself I’m familiar with from recent years. But the clown of 1999 butts through at points. The clown that fantasized in interviews about breaking his limbs onstage and professed that he saw his five-year plan as being diagnosed with a terminal disease so he could blow his head off onstage. That blunt, maniacal and, at times, wildly funny clown takes control sporadically during our interview. He compares Slipknot to a giant gumbo with different ingredients you can remove and substitute for the perfect flavor, none of which are wrong as such. But when it comes to big changes, he tells it straight: “people like me got to pull the trigger.”

He returns repeatedly to the notion of wheeling out the Slipknot hits in an encore on this tour – to ridicule it. In the old days, he says, he would have been a lunatic at the suggestion. Now, he’ll say a polite “no thank you” and just smirk before moving on. But he’s deeply defiant on the subject.

“I want to play songs that are dedicated only to that moment, and not give in and be a sellout and play ‘Duality’ at the end on fucking cheese ball shit,” he says, slowing right down to savour the insult. “Everybody leans into that cheese because they're weak.”

When you summon the mentality and “philosophy” (one of clown’s favorite terms) of a previous era, some of the outcomes can be unconscious. It certainly wasn’t clown’s suggestion that the Here Comes the Pain tour kicked off on 6th August in Noblesville, Indianapolis, at the Ruoff Music Center. The venue is significant to the band’s history. It was here during Ozzfest 99, when it was called the Deer Creek Music Center, that Slipknot played early on the second stage on 29th June – the day Slipknot was released.

On that day in 1999, clown remembers leaving the bus with Joey on his shoulders, discussing the show ahead, as they were accustomed to. They heard a shout of “Joey!” coming from 25 yards away and spotted a small group trying to get their attention. Up to that point, outside of Des Moines, Slipknot didn’t have fans. These kids had been out that morning, bought the album, and high-tailed it to the venue to intercept the band and get it signed.

“Joey and I looked at each other, and we're like, ‘It's official,’” remembers clown. “‘It begins today.’ The first stage was our whole life to get right there. Why was it that day? Because there was a barcode on the back [of the CD], and that's what made it official for the rest of the world. For the rest of the world to take us seriously, they needed that barcode. For us, we just needed to be there in person, in blood and flesh, which we were. So we looked at each other and we were like, ‘Holy fuck. Oh my God.’ We had the best show.”

There was one fan there with about thirty piercings in his face. Joey and clown were taken aback by how hardcore he was, already talking with knowledge and conviction about songs on the album. The maggots started breeding from that point, right up to the maggot with a pilot’s license who, earlier this year, performed a dive in his small plane to get a clearer photo of the mysterious billboard the band placed in the desert trailing their secret show at Pappy + Harriet’s. From the maggot with a gun in their mouth pulled back from the brink by the band’s music, to the wide-eyed fan transfixed seeing “Scissors” performed for the first time this tour, the message is always clear: We are not your kind.

For clown, bringing Joey up reminds him that the band has always given its best, but it’s not always been the best version of itself.

“I don't know, man, it's just like something that you had your whole life, that you lost, when we lost Joey,” he says. “And if everybody thinks about it, we really never talk [about that situation]. You can't find anything of us explaining all that, because it's nobody's fucking business, and he's our brother. And who knows, man, there might have been a chance in life. I don't know the future. There might have been a chance we would have gotten back together. I don't know. I can't tell you yes or no, but there's a better chance [of] yes [than] not because of friendship and growing older and talking and being able to understand things. So I just want you to know we're having a really good time with our music and with each other. We're all working really hard right now, really hard. As hard as it is to break in new philosophies, to do this setlist, to make new things, to have new people. It's so much work.”

If this anniversary tour feels like a reawakening, that’s partly because Slipknot was, and remains, a prophetic album. Slipknot exorcize their pain onstage but they also plough into it like a freight train. This manifests in onstage injuries: clown split his head open, not once, but twice, during their first Ozzfest tour. Sid's injuries are numerous, and his recent hospitalization from a bonfire explosion at home seemed itself like a weird callback to when he set himself and other band members on fire during that ‘99 era. There's a reason Here Comes the Pain is in the present tense.

“‘Here comes the pain’, not ‘There goes the pain’, or ‘We're going to mend the pain,’” says clown. “Or, ‘Hey, 25 years later, the pain's gone.’ 25 years later, on different mentalities we still use the number one mentality: Here comes the pain. It’s never going away.”

The original sample of the phrase used in “(sic)” is a proclamation from Al Pacino's character in 1993 film Carlito's Way. “You think you're big time? You're gonna fucking die big time!” he shouts as he's about to launch himself from a bathroom with a gun in hand.

The band's own tragedies seemed to be encoded in Slipknot: including the tragic deaths of Paul and Joey. The cover of the book Slipknot: Inside the Sickness, Behind the Masks by Kerrang! journalist Jason Arnopp, published in 2001, carries a quote from clown: "We’re going all the way – until one of us dies!"

“If you're human, and you have the human condition, and you have blood in your veins, and you live in this place – you have pain,” says clown. “And sometimes the pain is greater than the love. I can be in a great mood all day, but see a baby bird dead on the road and then just fucking the potential of what it could have been, what it missed out on, associating with my kids and my life and all the metaphors, I hardly can move from my place.”

Perhaps clown huffing on a dead crow he kept decomposing in a pickle jar backstage, during the band’s formative years in Des Moines, was a reminder of this inevitable demise. Each injury on stage was a little death and a reminder of the band’s mortality. But the pain hit as close to home as it could when clown’s daughter, Gabrielle, died in May 2019. The twentieth anniversary year of Slipknot was freighted with that pain.

“We don’t really talk about this,” clown told Arnopp for the book all those years ago. “But there’s not a day that goes by where, not only do I miss my kids, but I wish they weren’t born. I don’t want anything to happen to them and it scares me so much.”

In an interview with NME’s Steven Wells in January 2000, clown echoed this, and what he tells me today about seeing the dead bird. He has been remarkably consistent down the decades.

“I have three children and a wife and I love them very much,” he said to Wells. ‘But everyday I am reminded of how much fucking filth there is in the world. So much filth it depresses me. I’ll be in a good mood and I’ll turn around and see the filth and my whole day is ruined and I’ve immediately got to figure my children and how much pain and possibly how much suffering they’ve got to go through. Now I chose life and I chose life for them and I’m going to make the best of it, you know what I mean? But I hate every minute of it, actually.”

“I don't want you on my path,” clown tells me about people wanting to engage with him about losing his daughter. “I don't want you talking about my path. I don't ever want to see you on my path. You don't need to know about it. You don't need to witness it. You don't need to have anything to do about that path I'm on. You know why? Because it ain't going to change it. It ain’t going to get better. It's never going to be better. I don't even care if you've lost a child, you can't talk to me. Don't even think you're going to come up to me and tell me that time may make it help. No, no, no, no, nope. Not even time is helping. Nothing helps. Just regret and remorse and pain. And here comes the pain, man.”

September is a difficult month for clown, containing both his and Gabrielle’s birthdays. As he puts it, it’s a “loss” of a month. But a new grandchild also born into September is “a fabulous little salvation we've gotten, and it's beautiful because it helps the grief.”

This September also sees Slipknot embark on the second leg of their 25th anniversary tour in the US, including a grand return to Des Moines for Knotfest Iowa on 21st September.

Slipknot’s re-harnessing of their old rituals has set them on a vibration with the world again, ready to be “a vessel for how you’re feeling” in clown’s words. They’ve unbottled something. It might be good for us, it might be bad for us, but it feels truthful. Just as they started writing “People = Shit” on their T-shirts long before Iowa was released in 2001 and humanity showed its darkest face on 9/11, they are feeding on the raw energy of an unstable planet.

In 1999, clown once said that the artistic process begins with not giving a fuck about anything that is yours. He destroyed everything out of his sense of responsibility to reality. This is the philosophy that has run like an iron rod through Slipknot’s back. Because once you have nothing, you have to start creating again.

clown insists he hasn’t changed at all, but he’s learned that everything has its right place at the right time. Biding his time until the time is right.

Suddenly, the clown of zero compromise from 1999 is speaking to me again: “So, nothing derivative, nothing contrived, nothing even subjective. Full-on meaning or get out of my face.”