1992’s Candyman is as affecting of a movie as any good horror flick hopes to be; a haunting, hypnotic and bone-chilling experience that sticks in the mind due to both its frights and the way its social commentary feels so naturally well-ingrained into its story.

Based on Clive Barker’s short tale ‘The Forbidden’, which explored class discrepancies and urban development in Liverpool, writer and director Bernard Rose moved things to Chicago in order to add the American dynamics of race to the story’s themes.

Rose’s film follows a white woman named Helen Lyle (Virginia Madsen) who inserts herself into the space and stories of the infamous Cabrini-Green housing project, taking photos of the heavily graffitied walls and prying first-hand accounts of the area’s atrocities out of its residents in order to write a thesis and further her own success in academia.

Her research eventually leads her to the legend of Candyman, a vengeful specter of Black pain and trauma who has been receiving the credit for an alarming number of grisly murders, and whose very name strikes fear into the hearts of anyone foolish enough to utter it. Say it five times into a mirror and you’ll summon him - a mistake you won’t live to regret.

That original 1992 film has left a sizable legacy not just in the horror scene but culture in general. You’d be hard-pressed to find someone willing to play the summoning game in the mirror with you, and the very name Candyman fittingly has become somewhat of an urban legend in the real world just as much as it is in the world of the film.

In a post-Get Out Hollywood, with the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement and in the wake of 2020’s racial reckoning, it seems as good of a time as any then for a legacy sequel / soft reboot of sorts to expand on the original’s themes and add a contemporary context to the story.

Courtesy of Universal Pictures

Written and directed by Nia DaCosta, this new Candyman reclaims the legend so it rightfully belongs to Black people (as brilliant as Rose’s film may be, his perspective is still limited as he is a white man from London) and also puts the focus on Black characters.

Yahya Abdul-Mateen II (Aquaman, The Trial of the Chicago 7) stars as Anthony McCoy, a frustrated artist living in one of Chicago’s more gentrified spots. Anthony has grown tired of feeling like he needs to depict Black violence in order to make any kind of name for himself on the scene, but it’s seemingly all that the city’s white art critics and consumers are interested in.

An attempt at inspiration takes Anthony on a stroll through what’s left of Cabrini-Green, which has been bulldozed to the ground and exists like a ghost town in the shadow of the city’s modern development. It’s here that he has a chance encounter with a man named William Burke (the incomparable Colman Domingo), a surviving resident who shares with Anthony the terrifying story of Candyman.

The film updates the myth somewhat - while the original Candyman (played by Tony Todd) was the spirit of a 19th century painter who was murdered by a white mob, Burke tells the tale of a hook-handed man who handed out sweets to the children of Cabrini-Green before he was murdered by police. But both incarnations keep the essential part the same: anyone who dares to say his name five times in the mirror is doomed to meet their end.

Anthony is fascinated by the story but not respectable enough of its importance, using it as his latest project at his girlfriend Brianna’s (Teyonah Parris) art gallery and unwittingly releasing a dark and unstoppable force they can hardly comprehend, much less stop.

While the 1992 film could technically be considered a slasher, it mostly avoids the predictable trappings and rhythms of the genre and rarely feels like it’s part of it. DaCosta’s film on the other hand, is unapologetically in the court of the Slasher, and seemingly wants Candyman to join the ranks of Freddy Krueger and Jason Voorhees.

This makes for quite a lot of sequences of killing, some of which are gruesome enough for bloodthirsty audiences but most of which go for the arguably more tasteful approach of implying brutal violence rather than showing it outright. After considerable buildup, the camera often pans away from whatever horrific fate befalls Candyman’s latest victim, usually leaving us with only limbs or spilt blood in view.

Courtesy of Universal Pictures

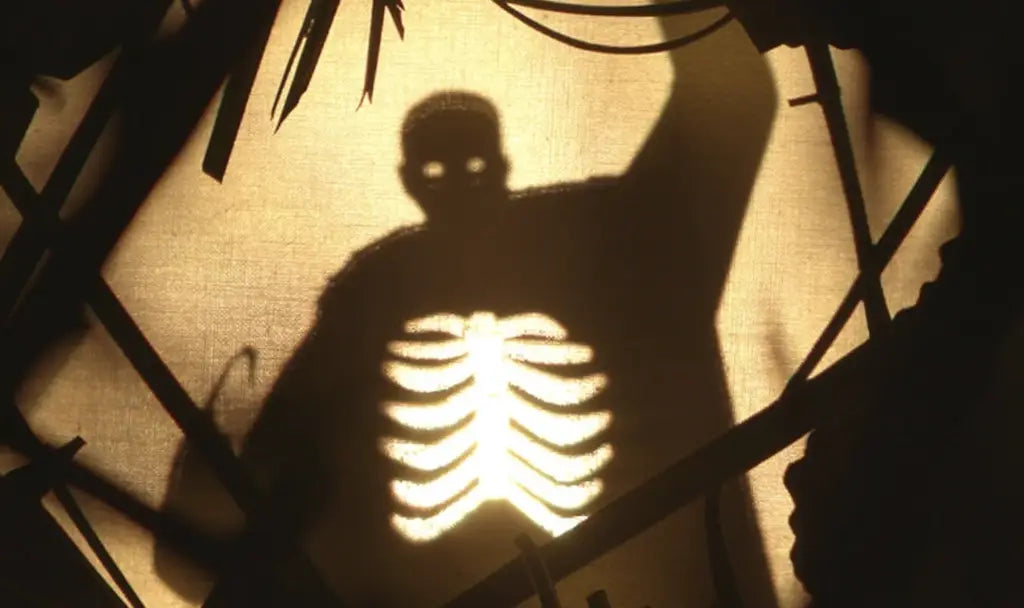

There are many ideas throughout DaCosta’s Candyman that are enthralling and many details that are brilliant. The way the overpriced lofts and condos of the city loom over the abandoned and rotting corpse of Cabrini-Green’s rowhouses and quite literally casts a shadow over it is a memorable and inspired image, as is the film’s use of shadow puppetry for its numerous bouts of exposition and storytelling.

The way Candyman’s victims are flung about by his hook resembles the way those puppets move, constantly invoking the film’s concept of mirroring and reflections that’s seen from the narrative use of actual mirrors, to the more figurative way it deals with it, all the the way to its inverted title sequence. The performances are great, particularly Abdul-Mateen’s shift in physicality as Anthony becomes entranced by Candyman much in the way Helen Lyle was. It calls to mind the methodical and unnerving movements of Michael Myers, but with a greater and higher purpose.

But it’s difficult to say whether all of these elements come together as cohesively as they could by the film’s end. It’s a dense 90-minute movie, one that bogs itself down not only with an overload of its own mythos and recappings of the first film, but also in trying to tackle so many different subjects and social issues to the point that it’s hard to discern what exactly it wants to say about them.

Things start to feel repetitive. The film’s observations on gentrification and connected issues, while absolutely correct in their stances, aren’t exactly revelatory and causes more than one scene to suffer from dialogue that feels awkward and unnatural.

The rules and workings of Candyman and his deeds somehow feels both under and over explained, with some specifics laid out in full detail while others are left frustratingly vague. There’s certainly a vagueness to the exact supernatural abilities of Candyman in the 1992 original, but it works in favor of that film’s mesmerizing atmosphere.

Here, it simply feels inconsistent with the rest of the film’s insistence on devoting time to explaining nearly everything else. But most of all, this new Candyman simply isn’t scary enough. That unpredictable and even at times sensual feeling of dread, sadness and terror that resonates so strongly in Rose’s film is sorely missed, as is Philip Glass’ transcendent score. The violence was shocking and impactful there; here it feels far too polished besides one successfully squirm-inducing sequence of body horror.

Courtesy of Universal Pictures

Candyman is undoubtedly worthy of a modern update that could secure its place not just in the gory revival of slashers, but also the supposedly esteemed halls of elevated horror with the way its social subtext is already baked into its premise. But DaCosta’s film, which was co-written by Jordan Peele and Win Rosenfeld, lacks the scares, emotions and thematic focus of other horror films that deal with similar issues of race and class. For every thematic beat or poignant shot that the movie is able to nail, two more feel like they get lost in the shuffle.

The film does manage to keep an emphasis on the power and significance of fables and myths and the dangers of letting them drift into memory or ignoring them outright. Again, there are plenty of aspects of Candyman that are strong individually, but things never quite gel together to become something as impactful as a film like this could be.

Perhaps it's due in part to the fact that the film was created before the events of 2020 (it was originally scheduled to be released in June of that year) and whatever reckoning it hoped to ignite pales in comparison to what people have now already been through. It's simply lacking the proper punch to the gut that it needs to feel like.

'Candyman' is now playing in theaters.