In the late fall of 2006, Type O Negative began writing their seventh and final album, Dead Again. Every weekday evening around seven o’clock, guitarist Kenny Hickey and drummer Johnny Kelly drove to singer and bassist Peter Steele’s house to pick him up for their writing sessions. Often they woke him up. If he was already up and about, it was usually for only an hour or two before they arrived.

At that point, Steele’s drinking was so bad that he had given up on driving. His car, which Hickey refers to as a ‘Sherman tank’-like vehicle, had been abandoned somewhere. The three of them drove across the bridge to their rehearsal room in Rockaway Beach.

For the self-styled ‘Lords of Flatbush’ (a neighbourhood in Brooklyn), leaving the borough to do anything was a bone of contention. In particular, keyboardist and longtime band producer Josh Silver was ‘dead set’ against it. He had started to train as an EMT, so only came to the sessions once or twice a week. If they couldn’t rehearse down the block and visit their favourite Chinese restaurant, what was the point?

Rockaway Beach is a summer resort on a sliver of land that is technically part of Queens. But Type O was there in the fall. Fall was their season. It was romantic and melancholy. The leaves were aflame on the trees. But over the winter months, Rockaway became an exposed, frigid and unforgiving place.

Each night, they set up in a rehearsal room measuring ten feet squared. They played at a relentless volume of 120 decibels. Only then could Hickey and Kelly recommence the arduous process of extracting riffs from Steele. Steele hated jamming like this. He loved consistency in songwriting. But the state he was in demanded tough medicine.

‘He wanted everything to be controlled,’ says Hickey on a Zoom call with me. ‘And mathematically based, because it was just part of his OCD. Jamming freely was against his nature. We're talking about a guy who liked to cut his french fries all the same size.’

When they started playing, they also started drinking. The clock ticked down until they were too inebriated to play anymore and began arguing instead. They left in a fury, before slowly calming down and starting the process again the following evening. It went on like this five days a week for over four months.

Hickey says it was a ‘brutal’ and ‘monotonous’ process: ‘it was definitely the most cumbersome record to pull out of him.’

It wasn’t all hard work. They were sure to bake laughs into the Type O experience. For them, mordant humour and deadly seriousness were often interchangeable. The rehearsal space was above a Chinese-owned Tex-Mex restaurant. Steele promptly hit on the proprietor. Unsuccessful, he then tried his luck with her daughter. The proprietor referred to him as ‘the big idiot’. (At 6’8”, Steele was a particularly big idiot.)

One night, Hickey and Kelly were eating in the restaurant and heard Steele’s bass amp roar to life upstairs. The ceiling started juddering. One of the ceiling tiles fell into the proprietor’s wok.

‘I know it’s that big idiot!’ she screamed. After that, the band had to relocate to another space across the street.

Steele was a larger than life character. Born Petrus Thomas Ratajczyk, he had Eastern European and Nordic ancestry. Maybe that inspired him to concoct a fictional country as a spiritual home for the band: Vinnland. He salutes his people in a made-up, Slavic-style dialect during passages in Dead Again songs ‘September Sun’ and ‘She Burned Me Down’. Growing up, Steele had five older sisters. He later spoke about spending hours hiding under their beds so he could grab their ankles and terrify them.

He craved attention as a child and got it in abundance as an adult. Type O Negative emerged in 1991 with their debut album Slow, Deep and Hard. The hallmarks of their sound were already in place: the lengthy, episodic compositions; passages of harsh brutality; and a gothic sensibility married to hardcore punk’s barbarism.

As they progressed, they refined what they were doing. 1993’s Bloody Kisses was a massive breakthrough. It had it all: alt-goth hit ‘Black No.1 (Little Miss Scare-All)’, the jocular contrariness of ‘We Hate Everyone’, and the arch blasphemy of ‘Christian Woman’.

The interplay between Steele, Silver and Hickey created a lush, panoramic soundscape. On 1996’s October Rust, Steele’s bass lines propelled the band forward. Hickey’s guitar and Silver's keys conjured the rest of the album's autumnal atmosphere. Sometimes, they swapped roles, and Hickey pinioned the melody in fifths, and major and minor thirds. Steele could then roam freely up and down the musical scale. He privileged high end, clearly articulated bass tones – awash with sustain, chorus and delay. Both guitarists were masters of wielding and manipulating feedback.

Though Silver frequented the Dead Again writing sessions less than the others, he always had a view on the parts. He was another outstanding musician and arranger. He created the accompanying and divergent melodies that made Type O’s music distinctive and truly theirs. Silver also helped Kelly work out drum parts. Dead Again is notable for being the only studio album to feature Kelly’s live drums. Previous albums used a drum machine. Kelly wanted the opportunity to play live drums on a record badly enough that they finally gave it to him.

Steele and Hickey’s voices worked well together too. They discovered their voices complemented each other on ‘Hey Pete’, a bastardised cover version of ‘Hey Joe’ by Jimi Hendrix (from their 1992 faked live album The Origin of the Feces). Hickey’s grittier, classic-rock howl was a foil to Steele’s mellifluous croon. On Dead Again, Hickey’s vocals shine on ‘The Profit of Doom’, ‘September Sun’ and ‘Some Stupid Tomorrow’.

On the second half of ‘Tripping A Blind Man’ from Dead Again, Hickey went a step further. He mimicked Steele’s vocal line on the guitar, talking along with him. It echoes the way Alice In Chains employs a talk box and the guitar follows the lead vocal on their classic song ‘Man in the Box’.

Fifteen years after it was released, Dead Again feels like an amalgam of all the eras of Type O. It has ten hefty songs but none of their (often dark or irreverent) interludes. It stretched to over 77 minutes long. They had never been fans of concision. Singles 'The Profit of Doom' and ‘September Sun’ were butchered for radio edits. When they went hard and fast on the album, it was even thrashier than the early days.

‘I think we did pull every trick out of the hat that we had tried earlier,’ says Hickey. ‘But I don't think any of it was deliberate. Because it was literally just off the cuff.’

‘She Burned Me Down’ seemed to be the embittered aftertaste of October Rust classic ‘Love You To Death’. Throughout his career, it felt like Steele needed to chase away shame and fear with what author D.H. Lawrence called ‘the fire of sheer sensuality’.

Sex and death obsessed Type O. ‘I’ll do anything to make you cum,’ Steele intoned in his unfathomably deep vocal register on October Rust’s ‘Be My Druidess’. As their career advanced, their songs became more about Steele’s struggles with substance abuse. 1999’s World Coming Down started with a doom-laden song called ‘White Slavery’, about his cocaine addiction. Steele referred to his time before using the drug as ‘BC’. On World Coming Down, he laid himself bare and flaunted his flaws. It says something about the severity of the album that its catchiest songs are called ‘Everyone I Love Is Dead’ and ‘Everything Dies’.

‘The band would tip back and forth between absolute realism and honesty, and fantasy,’ says Hickey. ‘October Rust I would say is where we take the plunge into total fantasy. Probably the most realistic, brutal albums are Slow, Deep and Hard and World Coming Down.’

Though Dead Again was a struggle, it was still a better experience than writing and recording previous album Life Is Killing Me. The 2003 record’s lead single was ‘I Don’t Wanna Be Me’. During recording, Steele simply didn’t want to be there. He had other preoccupations – partying, friends and women. Hickey admits that both of them were living a very unhealthy lifestyle. The result was their ‘weakest’ album, though Hickey still thinks 'Anaesthesia' is a great song.

A few years later, Steele's friends had disappeared. He had broken up with a girlfriend called Elizabeth, who haunts ‘September Sun’ and ‘Hail and Farewell to Britain’. The lyrics of the latter were also a goodbye to his former self. His only friends were his bandmates.

‘At that point he was not functioning unless he was removed from his house and taken to the studio,’ says Hickey. ‘The guy literally had one brain cell left. But, as fucked up as he was, in his defence, Peter could always compose.’

Struggling with his own demons and drinking, Hickey knows he was complicit in building up Steele’s image.

‘I called him "Rasputin" because no matter what kind of drugs you put in him, or whatever else, you couldn't kill him. Which, of course, is a mythology that built up over the years. But reality has to set in sooner or later,’ says Hickey.

Grigori Rasputin was a Russian mystic and political shadow operator from Tsarist Russia. In the figure of Rasputin, myth and reality were blurred beyond distinction. The band delighted in using a photo of him for the album’s cover.

As Steele’s life became more bleak, he reverted back to the Catholicism of his upbringing. ‘These Three Things’ is the dark heart of Dead Again. At over 14 minutes, it is long even by Type O’s standards. It’s a remarkable song: moving from outright dirge, through to passages of intense light and blackest night. In it, Steele puts forward a strident anti-abortion message.

‘The child is torn from the womb unbaptized/There’s no question it’s infanticide,’ it opens.

Defending the song afterwards, Steele explained it was aimed at those who use abortion as contraception after the fact. It also spoke to his own (Catholic) guilt about a decision with a former girlfriend for her to have an abortion.

‘I think that the song for him was about one of the deadly sins that he felt he committed, which was abortion. Basically murder in a Catholic’s eyes,’ says Hickey. Before adding: ‘He did a lot of things for the atmosphere and the effect of it too.’

Steele and Type O deliberately courted controversy. They kept it close at hand and played with it when they wanted. Their songs felt sincere, but Steele often coated them in irony. A cultivated bad attitude was present in the beginning of the band, in songs like ‘Xero Tolerance’ on Slow, Deep and Hard. That imagined Peter murdering an ex and her new partner with an axe. His lyrics were so caustic that he got branded misogynistic.

‘I admit I am a sexist,’ he once retorted. ‘I hate all men. I want to be the only man on this planet.’

On ‘I Like Goils’ from Life Is Killing Me he ran with this idea. He turned his fire on the unwanted advances from male admirers after he famously posed for Playgirl. ‘I’m quite flattered that you think I’m cute/But I don’t deal well with compacted poop,’ he sang.

By Dead Again, Steele was plagued by apocalyptic visions. During the writing sessions, he spoke of dreams about the end of the world. In one, he saw a meteor hit the moon and the moon explode, showering Earth in its debris. Fragments of biblical end-time imagery are strewn throughout the album. As well as weird references to Israel, at one point comparing the promised land to Area 51 (again, in ‘These Three Things’).

‘A lot of it is insane gibberish, because at that point he was a little out of his mind,’ says Hickey.

Steele liked to combine conflicting ideologies to create inflammatory imagery. Hickey remembers a tour in Japan where Steele made a pin badge for his hat which combined Communist and fascist symbols. Japanese airport security detained the band for an hour for that one.

‘Laibach was one of his favourite bands,’ says Hickey. ‘He loved stuff like that. To combine these different ideas, or these different political ideas together that would never go together. Otherwise, they're the complete opposite. That was the kind of shit that turned him on.’

Steele also loved the surrealism of the band Devo and their concept of de-evolution. He saw humanity as de-evolving into gibbering fools. He wanted to be their clown prince. Hickey laughs that in today’s climate, the band would probably get shot for their antics.

The gigs that followed Dead Again were, in Hickey’s words, ‘the worst touring period ever’. I saw the band at the London Astoria in the summer of 2007. The venue, like the band, is now no more. Steele was thin and looked ill, often sitting down for a rest on the drum riser. The setlist was challenging too, with ‘These Three Things’ played in its entirety. That night they held it together to play well. As they did at the Wacken Festival, memorialised in live tracks reissued with Dead Again. But often they couldn’t perform to an acceptable standard.

‘The first week, it would be four cases of beer, four bottles of vodka, three bottles of whiskey and four bottles of wine on the rider – all that gets drunk in one day,’ says Hickey. ‘Then the wheels fall off the bus – you have people going insane. They're going to have to start cutting stuff on the rider. As time progressed, we were trying to cut down on the booze to keep it together. It was very, very, very bad.’

Ultimately, some of the power of Dead Again is that it foreshadowed what was to come. ‘I can’t believe I died last night/Oh God, I’m dead again,’ goes the chorus of the title track.

‘For so long, we had been living in a near-death experience that we got used to it,’ says Hickey.

The band was fatalistic. They were all going to die someday. Sometimes they worried whether Steele would have a bad night and not wake up. But he always did. He seemed indestructible. Until he wasn't.

‘Sooner or later, you’ve got to pay the ferryman,’ says Hickey.

Steele died of sepsis on 14th April 2010. That was the medical cause, but he really died of the manner in which he lived. As he made it painfully clear in his music, life itself killed him.

Type O played their last show on Halloween the year before, at Harpos in Detroit. They had made it a tradition to do a mini-tour during the spooky season that was synonymous with them. ‘Halloween in Heaven’ from Dead Again was originally conceived as a tribute to murdered Pantera guitarist Dimebag Darrell. It evolved to became a roll call of famous dead musicians, including John Bonham, John Entwhistle, Bon Scott, John Lennon and George Harrison. The latter pair were Type O favourites. The ‘drab four’ were one of the few heavy bands to overtly incorporate The Beatles into their own compositions. Steele can jam (even if he still hates it in the afterlife) with his heroes now.

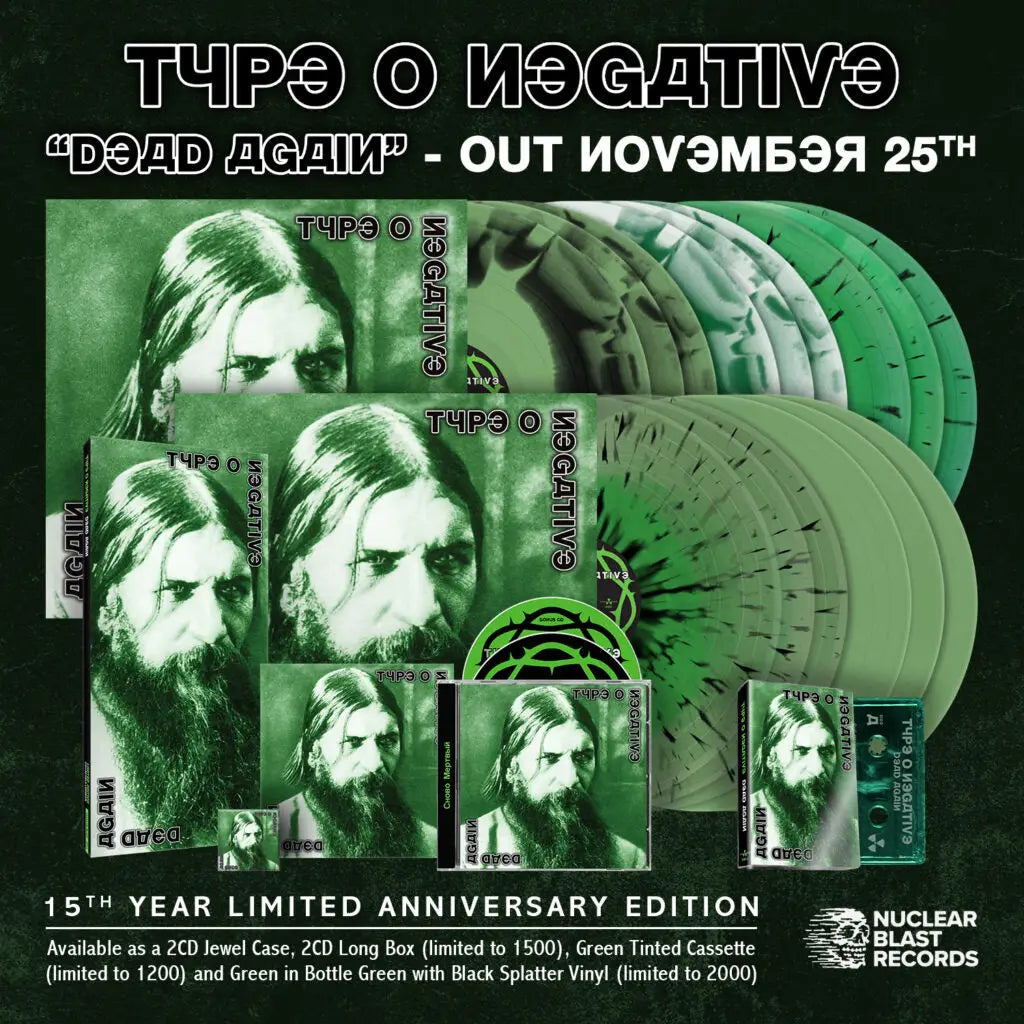

The re-release of Dead Again is a timely reminder of Type O’s genius. Hickey calls the album’s existence nothing less than 'a total miracle, an unbelievable miracle’. Thirty years after the band started their influence is everywhere, and yet nowhere. Their merch is still prominent amongst bands and audiences in both metal and hardcore communities. Elements of their sound and aesthetic are present in acts such as Unto Others and Code Orange. But no-one has ever really attempted to rip them off wholesale. The chemistry and charisma is impossible to replicate.

‘I like to think that part of it is like this sort of sub-underground, legendary kind of rock band,’ Hickey says of the band’s legacy. ‘Then the other thing is, I think that we never really sold out. We never got to a point where we wanted to sell out and become commercial. Or we never could anyway, so the band always stuck to its guns. As weird and as odd as the band was, I think that we really followed our instincts and the art the way it wanted to go. And I think that's shown through now. I think it paid off in the end. It's the long, hard way to achieve any kind of permanence. But I think it's working.’

Type O Negative’s Dead Again is being reissued by Nuclear Blast. Available now on all streaming platforms and available physically on 25th November - HERE