The horror genre has always thrived on exposing the dark undercurrents of institutions we take for granted - religion, family, corporations, the state. With Him, director Justin Tipping sets his sights on perhaps the most American institution of all: football. Not just the sport itself, but the entire religious, capitalist, hyper-masculine spectacle that surrounds it.

The film makes a bold bid to interrogate what we’re willing to sacrifice for glory, fame, and the bloodsport we insist on treating like gospel. And for much of its runtime, it’s a stylish and exhilarating enough descent into the cult of football. But by its end, Tipping and his team fumble the ball one too many times.

At the center of this modern parable is Cam (Tyriq Withers), a promising young quarterback whose obsession with becoming the GOAT is fueled by childhood trauma. He grew up watching his idol Isaiah White (Marlon Wayans, in a career-highlight performance) score victory at the cost of suffering a near-fatal injury on the field. To Cam’s father, the moment was proof of what “real men” do: sacrifice their bodies for the glory of the game. “No guts, no glory,” he tells his son. It’s a mantra that haunts Cam as he grows up and rises toward stardom, a reminder that greatness is supposed to demand pain, blood, and ultimately, pieces of yourself.

The film immediately establishes itself as a sensory onslaught. Early scenes capture the overwhelming chaos of a young player’s life as Cam is prepped for fame: the endless noise of agents, fans, coaches, and corporate sponsors pulling him in every direction. Tipping and editor Taylor Joy Mason lean into stylish, overstimulating montages of flashing lights, deafening cheers, and rapid-fire dialogue. It feels almost too much to take in by design. Him thrives on recreating the claustrophobic pressure of modern celebrity, filtered through the uniquely brutal lens of football culture.

It’s here that the film starts layering in its horror. Cam can’t find a moment alone. He’s constantly surrounded, constantly expected to perform, constantly reminded of what others - family, teammates, fans - believe he owes them. When he suffers a traumatic brain injury just as his career is about to explode, he’s offered salvation by none other than Isaiah himself. Now reclusive and eccentric, Isaiah offers to train Cam in secret at his desert hideaway. “His fans are like a cult,” someone warns, and it isn’t far from the truth.

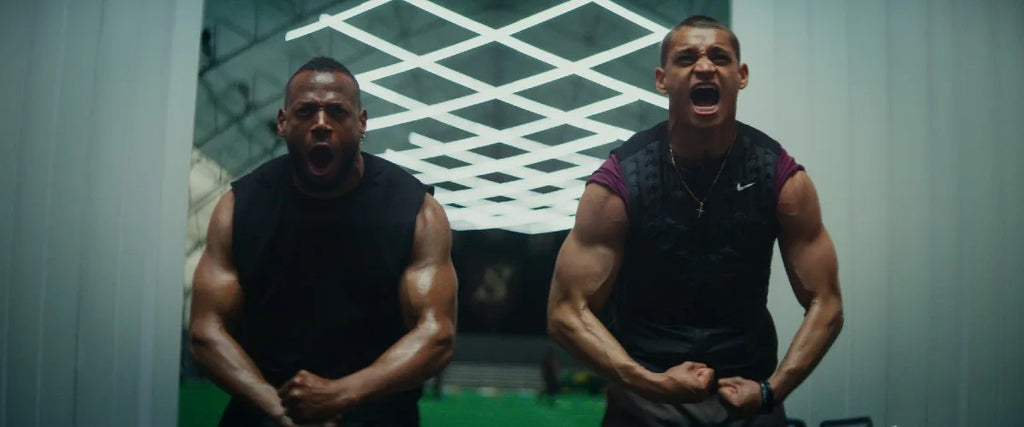

Wayans absolutely devours this role. Isaiah is both mentor and tormentor, a figure who sees himself as the gatekeeper of football’s legacy. His training methods border on sadistic: Cam is subjected to humiliation rituals, dehydration under the desert sun, and philosophical speeches about sacrifice delivered between torturous drills. “Would you rather never get tired or never get injured?” Isaiah asks before launching Cam into one of the movie’s most disturbing sequences. Wayans’ charisma makes it impossible to look away, even as Isaiah’s intensity curdles into menace. His wife Elsie (a scene-stealing Julia Fox as a social media wellness influencer) provides occasional levity, but she’s as complicit in the cultish atmosphere as anyone else.

Withers attempts to match Wayans step for step, delivering a striking physical performance that makes Cam’s exhaustion, pain, and longing for solitude deeply felt. His piercing eyes convey more than the script often allows him to verbalize. Unfortunately, that script is where Him starts to falter. For all the film’s thematic ambition towards masculinity, race, capitalism, religion, and the deification of athletes, it rarely digs as deep as it should. Cam’s family, particularly his mother, remain frustratingly underdeveloped, robbing his supposed sacrifices of emotional weight. One of the main lessons here is that family is the ultimate priority, but we’re never given enough reason to believe in or feel that for Cam himself.

Still, the filmmaking brims with verve. The editing and sound design are sharp, the imagery striking, and the tonal tightrope between psychological terror and dark satire is held for longer than expected. Tim Heidecker even shows up as Cam’s bumbling manager, offering a warped sort of comic relief that fits the film’s uneasy balance. It could’ve benefited from more of the energy that Heidecker brings to his limited screen time. The movie isn’t conventionally scary, but its psychological dread and grotesque exaggeration of football’s already harsh culture carry plenty of bite.

Where Him really collapses is in its third act. After building a tense, stylish critique of football-as-cult, the film abruptly shifts into over-the-top spectacle. The style goes into overdrive while the ideas fall apart, culminating in a finale that feels tone-deaf to the rest of the movie. A “Last Supper”-styled tableau is trotted out without having been earned, and the climactic violence lands less like a natural conclusion than a desperate attempt at badass genre iconography. Instead of deepening its ideas, the film starts over-explaining them, only to undermine everything with a finale that seems confused about what it actually wants to say.

The result is a messy finish that risks souring the whole experience. A bleaker, more nuanced ending could’ve tied the film’s themes together in devastating fashion. Instead, Him goes for hollow spectacle, leaving its satire half-baked and its characters undercooked. By the time it reaches its conclusion, the movie’s earlier psychological terrors and social commentary feel like setup for a payoff that never comes.

And yet, for all its flaws, there’s still a lot to admire. The central performances are outstanding, the direction has real style, and the concept itself remains rich with potential. As a cutthroat, exaggerated mirror of football culture, Him is often thrilling to watch, even if it doesn’t fully deliver on its ideas. The good outweighs the bad, but just barely. There’s just too many factors that hold the film back from greatness. Like Cam himself, the film sacrifices too much of what matters for a shot at glory, and winds up limping off the field instead.

‘Him’ is now playing in theaters.