The world of fashion, particularly the niche of streetwear can be an especially fickle circle. The nature of the community is fast-moving, predicated on remaining ahead of the curve, anticipating trends and adaptable in a way that often prompts drastic change.

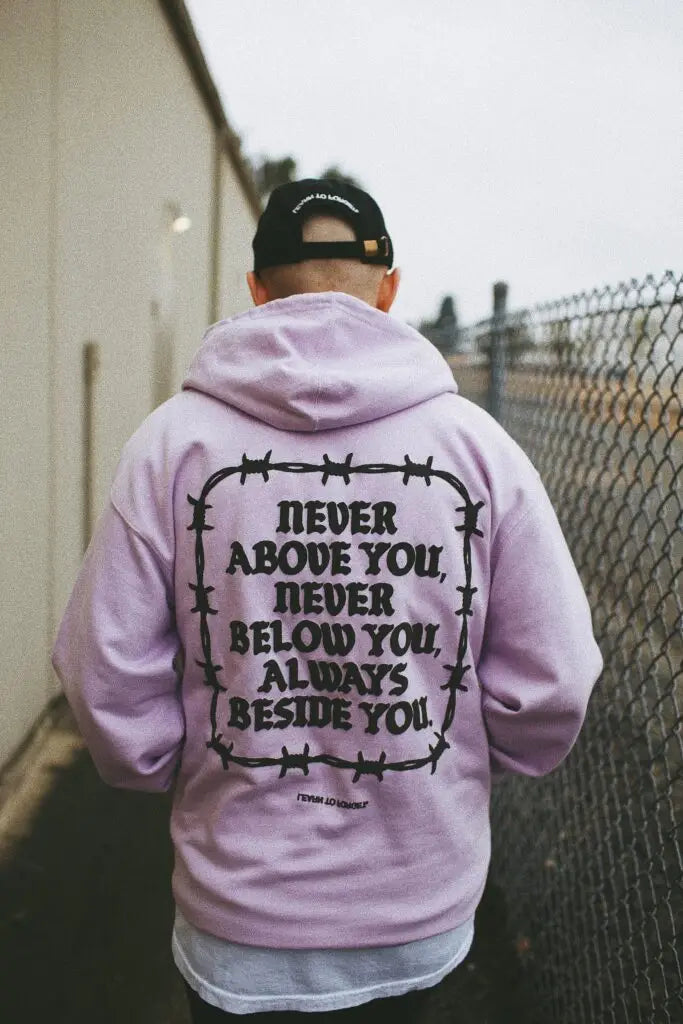

That sort of chameleon culture is directly at odds with the sub-circles at the core of Southern California brand Learn to Forget. Raised on a steadfast foundation rooted in the confrontation of punk, the aesthetic of graffiti and the ethos of street-level skate, the brand was forged by Reilly Herrera of Night Verses and Mike Cambra of legendary punk unit Adolescents.

Thriving in the margin, the label has continued an earnest, upward trajectory for well over a decade on their own merit, emerging from their humble garage-based roots to one of the space's most credible names. Fiercely independent and entirely hands on, Herrera and Cambra's combined creative bandwidth has been poured into LTF - a definitive passion project that speaks to the kind of education that could only come from a first-hand, immersive perspective of the culture that inspired them.

Navigating the learning curve of Learn To Forget, the brand has had to figure out how to adjust to their incremental growth, balance their musical endeavors and continue to keep the brand viable in a way that resonates with a cross-section of consumer that value fashion, yet can easily smell a fake.

Among the intangibles that best conditioned Learn To Forget to succeed - their ability to prioritize authenticity have been among the most important attributes in their longevity. Though fashion is about being timely with trends, that contrast with the tradition of punk, graffiti and skate make for a difficult, near impossible balance of the two. However for Herrera and Cambra, their subcultural pedigree, in tandem with their passion for the details of fashion, make for a creative combination that have fueled their brand's steadily climb rather than skyrocket.

That growth, gradual and genuine speaks to the core of Learn To Forget. Plenty of band guys drop their name into the mix, hock a few t-shirts and ride that wave - few truly invest their creative identity into the label the way Reilly Herrera and Mike Cambra have.

As one half of the duo at the core of the brand, Herrera spoke about the journey of Learn To Forget thus far, and how the growth of the project is directly correlated a simple premise - posers are easy to identify.

During it’s infancy, what was most important to the core identity of LTF as a brand? What were the things that were non-negotiables for you in establishing the company and it’s identity from the very beginning?

Herrera - During LTF’s infancy, the most important part of our identity was staying true to the influences in both of our lives that made us want to start LTF in the first place. Underground graffiti and punk-rock were the communities we grew up in, and that shaped both of our world views as we got older. The most important thing for us was to only make products that we, and our friends would actually wear - especially when we started the brand.

Given that the brand has been In the streets for nearly a decade, how do you feel like LTF has evolved? More importantly, how do you think it has remained true to it’s initial identity?

Herrera - I think the main piece of LTF’s evolution was moving into the wholesale business around 2019. We went from selling in one skate shop and two graffiti shops around OC & LA, to being sold in over 300 stores worldwide as of last year. Luckily for us the main influences behind LTF, graffiti and punk rock, never really go ‘out of style’. Even as trends change, those are timeless pieces of culture, especially in streetwear. While we always have to adapt to a certain extent, I think we’ve lucked out a bit that our initial identity hasn’t really had to change in order to stay relevant.

While there are plenty of band guys that have tried their hand launching a brand few people put in the kind of sweat equity you and Cambra have. What is the balance like in juggling the rigors of being a touring musician while still keeping your finger on the pulse to ensure LTF is always at its best?

Herrera - It is definitely a cliche, especially in the instagram / social media age - for band guys to start random clothing brands. The main difference for us is that I have always actually been involved in design and streetwear since I was little kid. I also design every single piece for LTF. From the graphics to the cut and sew pieces, I design everything and over see all the production too. It’s not some hired gun making random shit for random band members to sell low quality print-on-demand shirts to their band’s fanbase. We actually didn’t even use our band’s reputation to prop up LTF at all for years. We wanted LTF to stand on it’s own as a brand before we let people know what bands we played in.

Early in the brand when Mike and I were both on the road for 6-8 months a year, it got insane trying to keep up. We would book trade shows for LTF, and then a tour would pop-up and we’d somehow have to facilitate showing a new season at a trade show while Mike and I were both on tour somewhere in Europe or something. It was, and is, very stressful, but luckily we both have insane work ethic and we’ve made it work. It makes it easier that we both know we’re privileged to even be in a position where we can make music and create stuff with LTF that we truly love. When covid hit, things got tough on the music side of things - but also opened a lot of time for LTF. So that was kind of a blessing in disguise for focus on the brand.

As a touring musician, you have a very unique vantage point of various communities and subcultures. Has that different understanding of the world influenced what you are doing with LTF?

Herrera - Definitely. I actually got the idea to start the brand after going to the Carhartt WIP boutique in Koln, Germany while on tour. The general aesthetic and clothing itself was super inspiring, but didn’t necessarily translate to what I could do with my band, Night Verses. When I got home from that tour, I taught myself Adobe illustrator and began designing stuff that would eventually become LTF. Also just seeing different fits, clothing and trends in different countries is super interesting, to me anyway.

LTF lands on a cross section of punk, graffiti, and skate. These are all their own communities, their own cultures and you manage to connect with them all. How important is authenticity in that equation?

Herrera - The authenticity of punk, graffiti and skateboarding is probably the single most important thing of each of those communities. The second anyone can smell any bullshit, you’re pretty much done. I’ve seen repercussions of it in real life, and in much more serious circumstances than someone thinking your brand is ‘lame’ or your band ‘sold-out’ or something.

Especially with graffiti for example, it’s rooted gang culture in Southern California. If you’re not coming correct and you get caught up saying the wrong thing to the wrong person - shit can get real and you pay for it. Growing up doing graffiti, I’ve seen gnarly shit go down first hand. Stuff like that is a constant reminder that being inauthentic or misrepresenting something isn’t really an option for LTF. That’s why we don’t shy away from some fun graphics and PMA messaging too, because that’s genuinely who we are. If we just tried to be super gangster, tough-guy hard-asses with the brand, it wouldn’t be completely honest. We grew up as punk, stoner, tagger, skater kids in Orange County. It’s a fine balance but it’s not hard for us to keep it real.

When it comes to collaborations, LTF seems to prioritize quality over quantity. You have teamed with the likes of Smiley, Never Made and even Pabst Blue Ribbon. Given how prevalent the collab is especially in streetwear, how do you approach teaming your brand with anyone else? What is the baseline criteria when it comes to finding who you want to work with?

Herrera - Thanks. We definitely don’t want to over-do the collabs, but they are very important. Having someone like Pabst co-signing LTF for example, is crucial for a brand like ours to grow. Even if it’s just a perception thing for most people. As far as criteria, we try to not over think it and they come pretty naturally. It’s a mix of who approaches us to collaborate, if we like them as people, and if their companies’ values mirror ours. Luckily everyone we’ve worked with so far has been exactly that. Everyone has been fun to work with, and very supportive of our direction creatively. It hasn’t happened yet, but if something seemed off, or if someone was trying to change our ideas in a non-constructive way, we probably just wouldn’t do the collab.

Do you have to approach LTF with the same kind of brand integrity you do with your bands? What are similarities there? What are the very clear differences?

Herrera - The overall approach of LTF is very similar to both Mike and my bands’ in ethos. The main difference is the history that follows both of our bands, and it’s a much more delicate situation to change creatively when you have that. With LTF, Mike and I can make decisions very fast and take risks creatively - but that’s also a function of there being less consequence. With LTF, we put out 4 full seasons, 2-3 collabs and capsule collections in-between seasons in one year. With Night Verses, or Adolescents - we’ll work on an album for 3-4 years, and that album will have 12 songs on it. Taking the same risk on one or two graphics versus taking that risk on one of out 12 songs is just a lot more serious, I guess. A few good or bad songs can shape the next 4 years of your band. I love clothing, design and streetwear, but in the end music is just more important. Music creates the lens we view and create clothing through I suppose.

Particularly with streetwear, when a brand becomes too accessible, it tends to fall off. How do you find that balance of being visible and elusive at the same time?

Herrera - It’s similar to a band ‘selling-out’. If a band changes their sound completely to appeal to more people, you can fall off in the eyes of your core audience. If a band happens to get huge while being themselves, it’s not really selling out - but lots of the initial fans still will drop off because it’s popular now. It’s the same for streetwear brands. For example, when we first opened to Zumiez, they were (and are) awesome and want us to be ourselves completely. So much so that we ended up getting a C&D for one of our designs, and eventually had to pay a settlement that almost ended the brand entirely. That was a case of us being ourselves, and Zumiez being open and punk enough to take a risk on a small brand. We didn’t change a thing and they embraced that which is awesome in my opinion.

Luckily nowadays I think the notion of falling off and selling-out is slowly going away though. It can be a good and bad thing, but overall if it lets streetwear brands and artists be themselves without worrying as much about it, that’s cool with me. If someone decides to be lame and change for fame or something, I have faith that people will see through that shit eventually.

Do you have a shortlist of other brands and bands you’d like to work with?

Herrera - Definitely. Brand wise we’d love to collaborate with - Dickies, Doc Martens, Brixton, Liquid Death, Brain Dead and Obey to name a few. For bands - Sex Pistols, The Casualties, Rancid and The Germs would all be really cool.

What has been the most significant stride LTF has made thus far? Do you have a moment where you felt like the project that started in the garage reached a new level?

Herrera - The most significant stride for LTF I think was when we did our first year of trade shows. We were super naive at the time, but we figured out how to present the brand to retailers and release seasonal collections. After getting legitimate accounts, we literally moved out of the garage and into a warehouse. It kinda forced us into becoming a real company. We made a ton of mistakes, and i’m sure we’ll make more but that was the tipping point where we realized we could make something special out of this brand.

“Preserving underground ideals in an increasingly inauthentic world.” | Est. 2013